3Dfx Interactive: Gone But Not Forgotten

Founded in San Jose, California in 1994 past a trio of former Silicon Graphics employees, 3Dfx got its start making hardware for arcade machines. The company'due south kickoff-gen Voodoo chipset powered arcade hits similar San Francisco Rush, Water ice Home Run Derby and Wayne Gretzky's 3D Hockey. Just by the second half of 1996, retentiveness prices had dipped significantly which turned 3Dfx's attention to the consumer PC market.

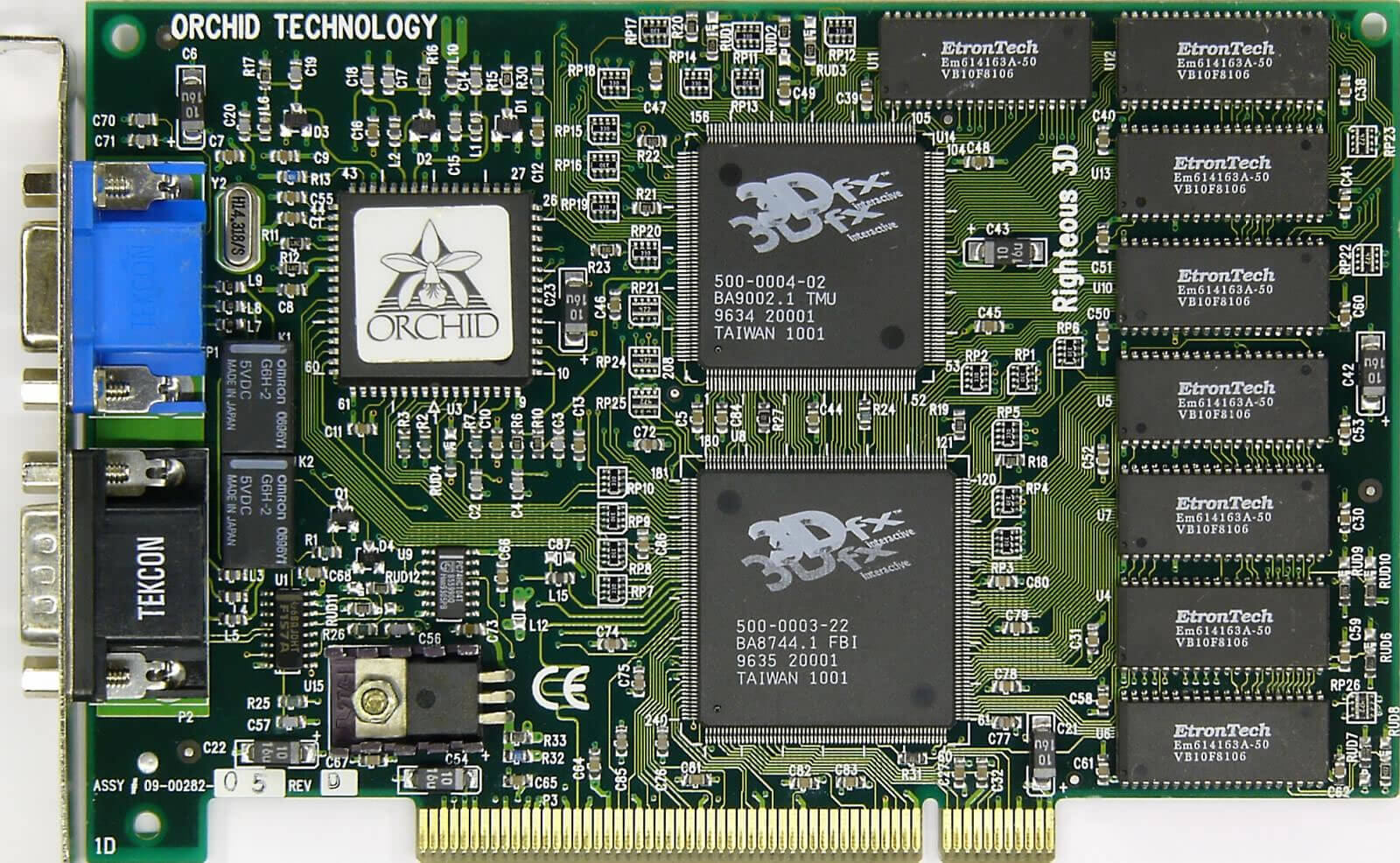

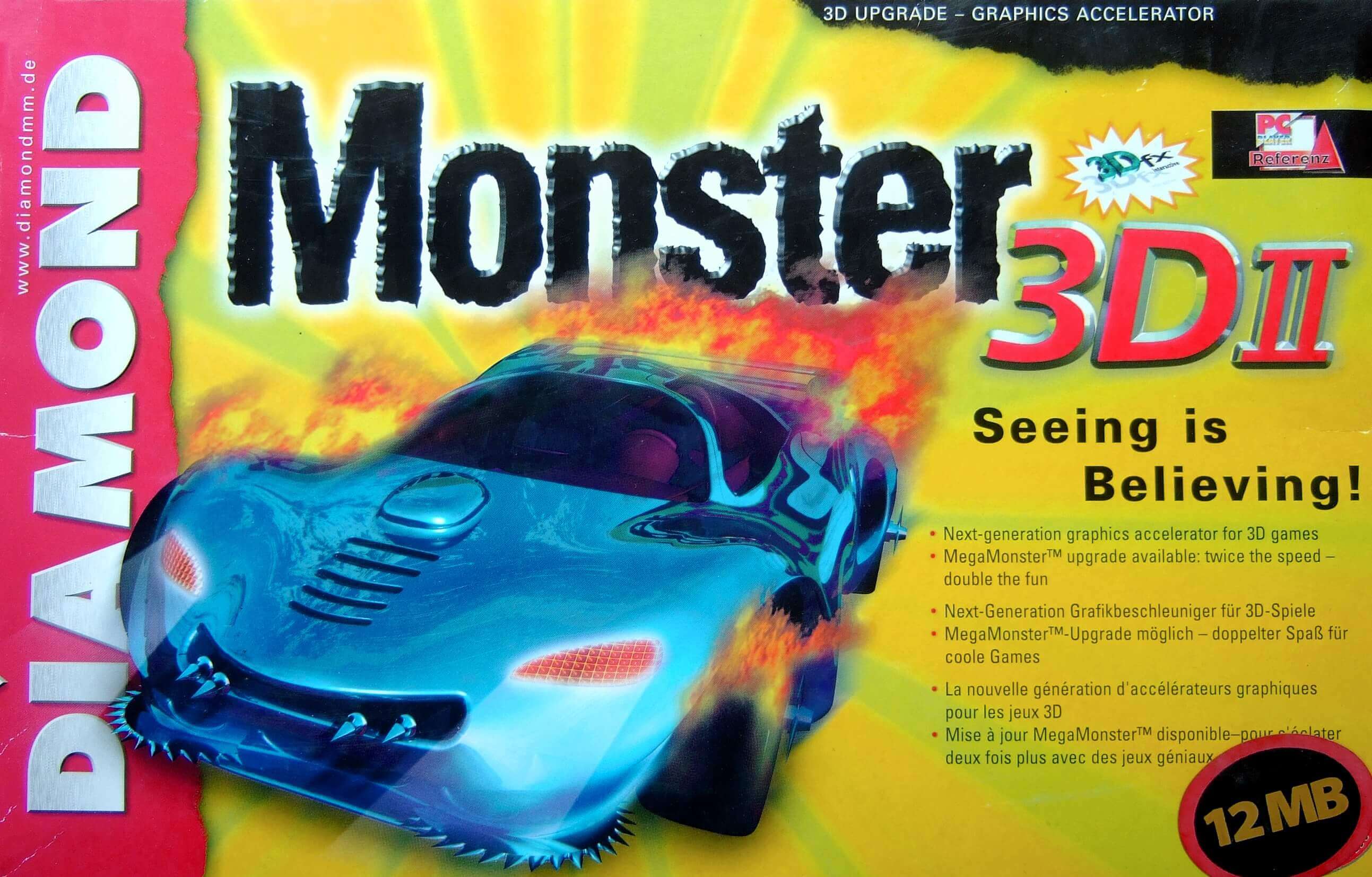

3Dfx's Voodoo graphics consisted of a 3D-only add-in card that required a VGA cable pass-through from a separate 2d carte du jour to the Voodoo, which then connected to the display. The cards were sold past a large number of companies. Orchid Technologies was offset to market with the $299 Orchid Righteous 3D, a lath noted for having mechanical relays that "clicked" when the chipset was in use. That card was followed by Diamond Multimedia'south Monster 3D, the Canopus Pure3D, Colormaster Voodoomania, Quantum3D Obsidian, Miro Hiscore, Skywell Magic3D, among others.

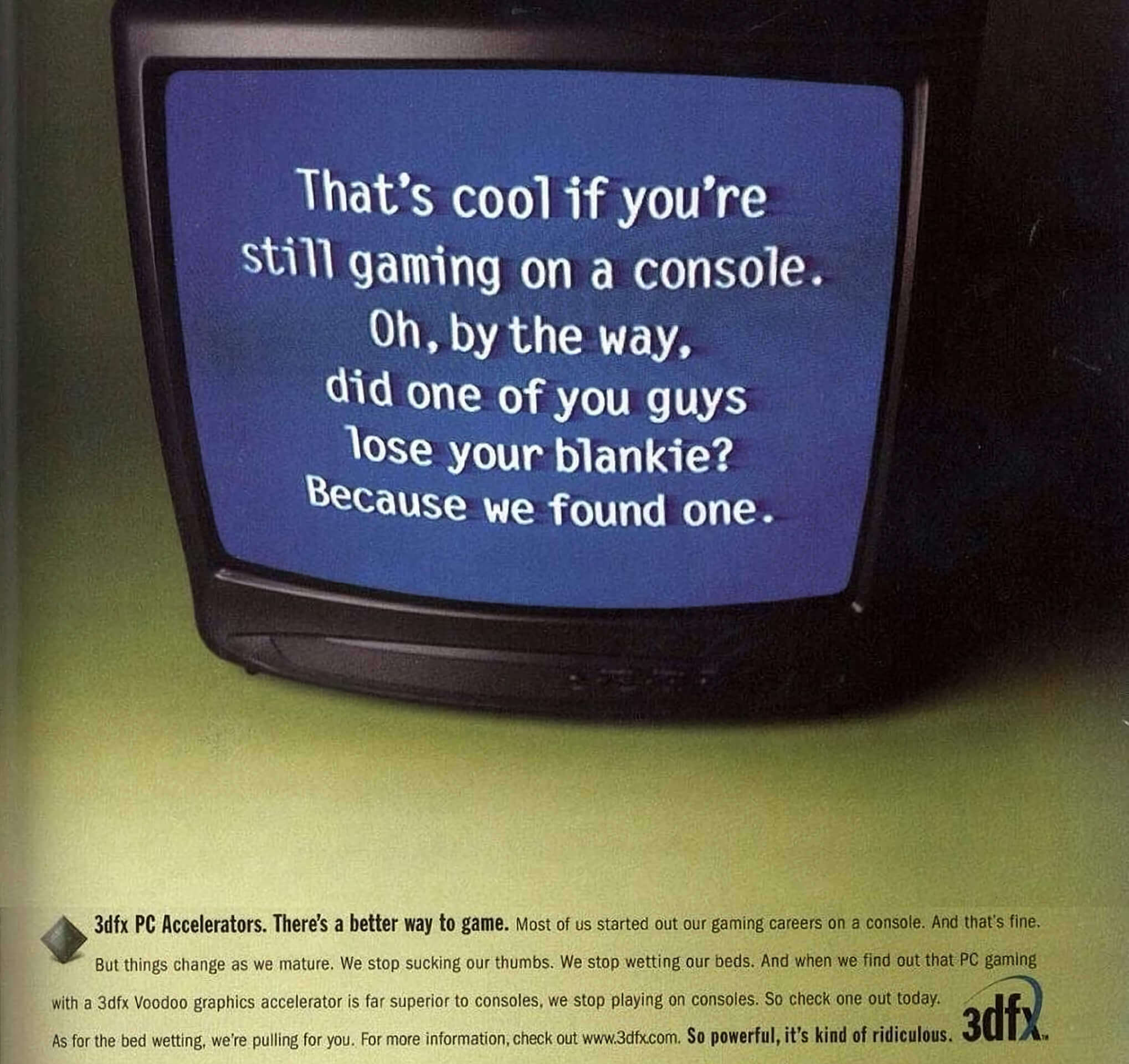

Voodoo Graphics revolutionized personal reckoner graphics almost overnight and rendered many other designs obsolete, including a vast swathe of 2D-only graphics producers. The 3D mural in 1996 favored S3 with around l% of the market. That was to change shortly, withal. It was estimated that 3Dfx accounted for lxxx-85% of the 3D accelerator market during the heyday of Voodoo's reign.

Eventually well-nigh of 3Dfx'due south competition came from companies that were already established in the market producing second graphics, and were meaning to produce philharmonic cards capable of 2nd and 3D. While these products didn't match the paradigm quality or functioning of Voodoo, their lower cost points and ease of use made them a hit with many OEMs. Need and public's involvement was there for the taking.

At the time, 3Dfx appeared to be in a unique position where it didn't brand graphics cards directly, simply sold its chipset to tertiary-political party OEMs to utilise in their own branded cards. The company thought this was an upshot which would attempt to accost after in its life, merely more on that in a chip.

3Dfx'southward answer to the combo bill of fare came a year later with the launch of the Voodoo Blitz, which paired its original Voodoo accelerator with a 2nd graphics chip on the aforementioned lath. The Blitz carried the same specifications as a standalone Voodoo just because it had to share retention bandwidth with the 2D chip, performance suffered. 3Dfx attempted to remedy this with subsequently revisions featuring more memory and higher clock speeds simply information technology was all for nix. The Voodoo Rush was discontinued less than a yr after launch.

On a personal note...

The December 1995 issue of GamePro mag featured a slice on DigiPen, a school in Vancouver that teaches video game programming. News of this "Applied Computer Graphics" school couldn't have come at a better time as my reckoner teacher had just issued an assignment regarding our dream task and how it might relate to applied science. I knew correct then and there what I was destined to exercise.

I'd been into video games for as long every bit I tin can remember. For a brief catamenia in the mid-80s, my aunt endemic and operated a video rental shop. Information technology was the sort of shop you'd find in whatever small town earlier Blockbuster monopolized the industry, with a respectable option of movies and – nigh importantly for us kids – Nintendo games. This only further solidified my interest in gaming.

I was fully enveloped by the late 90s, having laid claim to virtually every major console on the market. Nary a week would go past that I didn't receive at least a few issues of the latest gaming mag in the mail. Heck, I even circled release dates on my agenda and counted downward the days until launch in earnest.

Then there I was, an impressionable 13-twelvemonth-one-time in computer course with his entire life already charted out. I'd finish grade school, get accepted into DigiPen, graduate with some sort of caste and commencement living the dream of making video games.

In hindsight, that's probably how it would take played out had my other interest – the personal computer – not intervened.

I got my first computer in 1998 and it literally changed the entire trajectory of my life. I was still into gaming, mind you, simply the focus immediately shifted from consoles to the PC and it didn't take long to realize that my AMD K6-2 CPU with 3DNow! educational activity gear up needed some assist in the graphics department.

Enter 3Dfx Interactive.

The meridian of 3Dfx's relatively curt run – and where my story intersects with them – came in 1998 with the launch of the wildly successful Voodoo2. Congenital on a 350 nm manufacturing process, the Voodoo2 upped the ante with faster core and retention clock speeds of 90 MHz, respectively, up from 50 MHz on the get-go-gen Voodoo. In that location was simply goose egg that could compete with it, let alone when a game had implemented the proprietary Glide API (before Direct3D and OpenGL were seen every bit standard).

3Dfx also added a 2nd texture mapping unit of measurement in Voodoo2, which allowed two textures to be drawn in a single pass without a performance hit. They went dorsum to being a pure 3D accelerator, and the work put in resonated with gamers.

3Dfx's Voodoo and Voodoo2 chipsets are widely credited with leap-starting 3D gaming. Some even consider this period to be the golden era for PC gaming with titles like Quake, Quake two, Need for Speed II: SE, Virtua Fighter 2, Resident Evil, Tomb Raider, Diablo II, Unreal, and Rainbow Half-dozen all effectively making great use of the Glide API.

Equally Shamus Young so eloquently put it, "information technology was later on the rock age of DOS, but before the four horsemen of bugs, DRM, graphics fixation, and console-itis came in and fabricated a mess of things." For a deeper dive on this subject, cheque out our compilation of some of the best 3Dfx Glide games ever created.

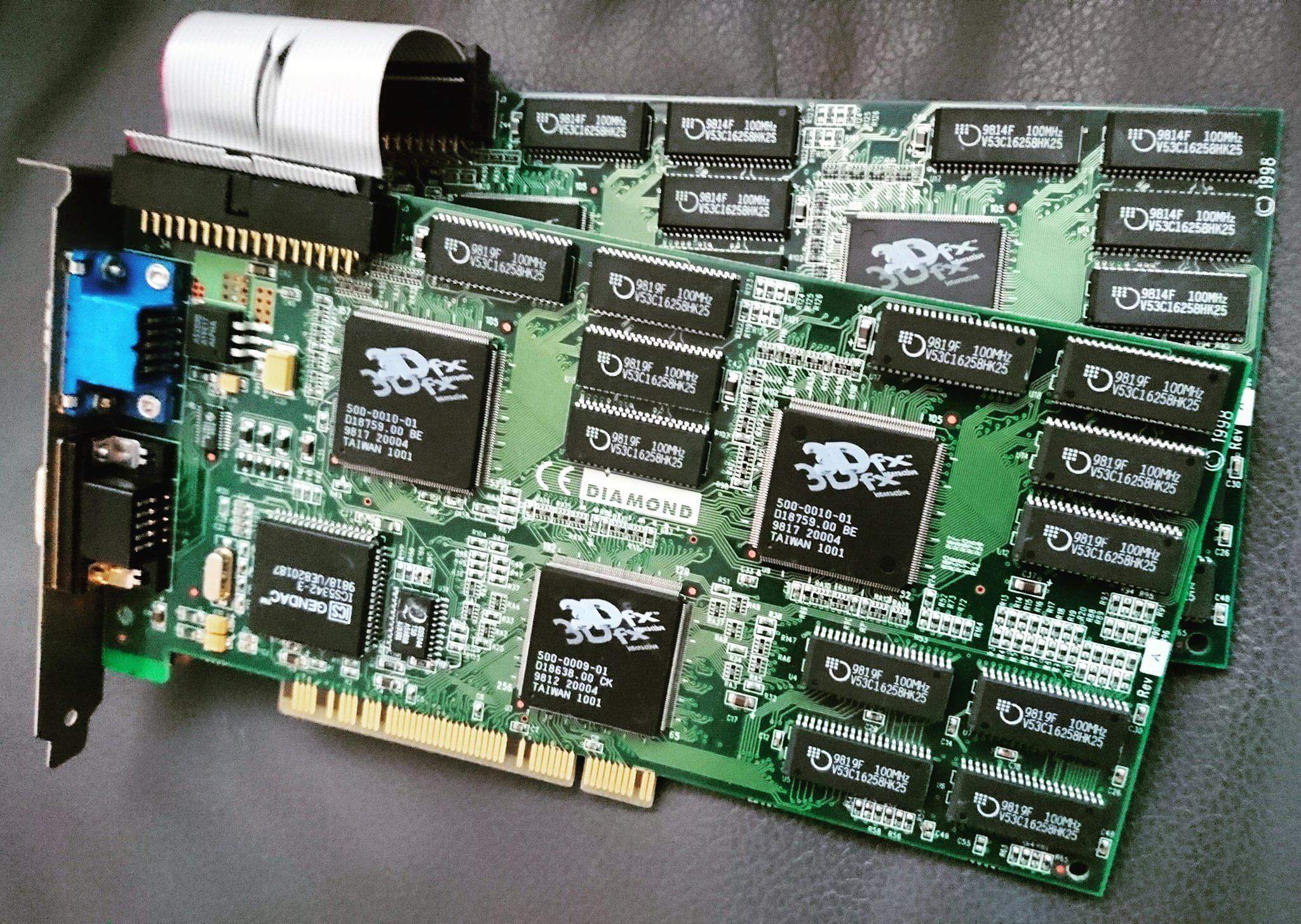

The Voodoo2 was too noteworthy in that it introduced SLI (Scan-Line Interleave), a process in which 2 Voodoo 2 cards could be linked together and run simultaneously to theoretically double the graphics processing performance. SLI allowed for higher resolutions, upwards to 1,024 10 768, but compatibility issues and the sheer cost associated with ownership two high-end graphics cards kept the feature squarely in the arena of enthusiasts and hardcore gamers.

SLI would get a mulligan years later courtesy of Nvidia. Now known as Scalable Link Interface, the thought backside the modern implementation is the aforementioned although technology that powers it is quite different than what 3Dfx first introduced.

"... we were doing tests on a very popular game called "GL Quake" and it was running at 120 frames per second, which is but giddy, I hateful nobody's going to run a game and add at that kind of frame rate or want to, just what information technology illustrates is the headroom that'due south available for developers" -- taken from the 3Dfx Interactive Documentary circa 1997

3Dfx would revisit the second / 3D combo card idea with the Voodoo Banshee and fifty-fifty submitted a design for Sega'southward Dreamcast game console, but was ultimately passed over in favor of a chipset from NEC. Things only went downhill from there every bit 3Dfx decided to acquire video card manufacturer STB Systems for $141 one thousand thousand in a bid to make its own video cards rather than continuing to serve as an OEM supplier.

In raw 3D functioning, the Voodoo 2 had no equal, but the contest was gaining ground fast. Amongst increasing competition from ATI and Nvidia, 3Dfx looked to retain a higher profit line past marketing and selling the boards themselves, something that was previously handled past a lengthy list of lath partners. That's where the STB acquisition made sense, but the venture proved a giant misstep as quality and cost of manufacture from the foundry used past the company could not compete with TSMC (used by Nvidia) or UMC (used past ATI).

Many of 3Dfx's former partners formed ties with Nvidia instead.

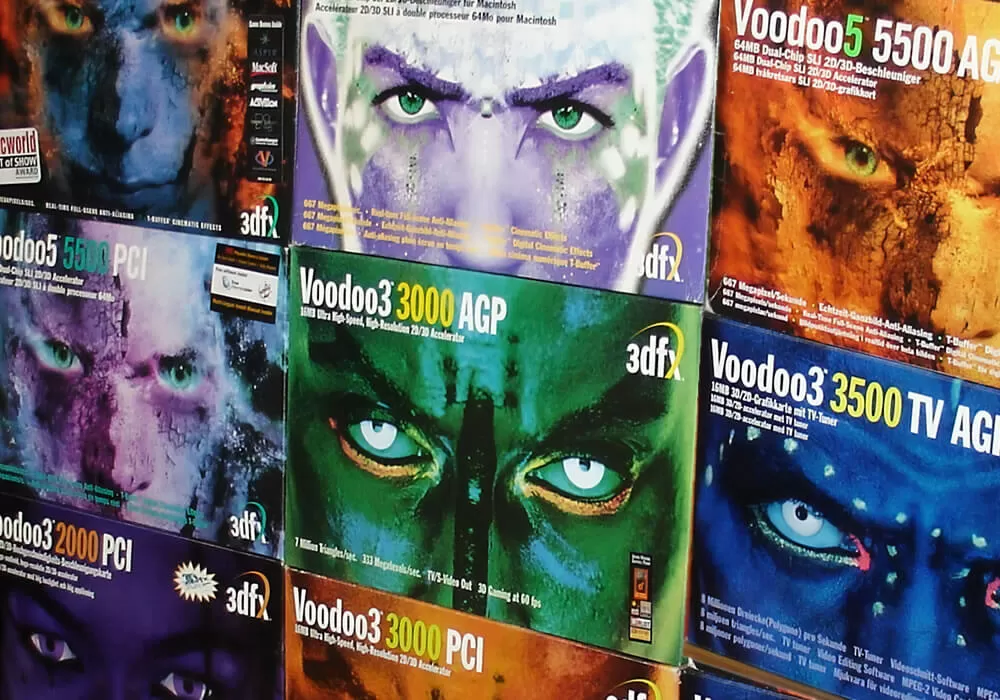

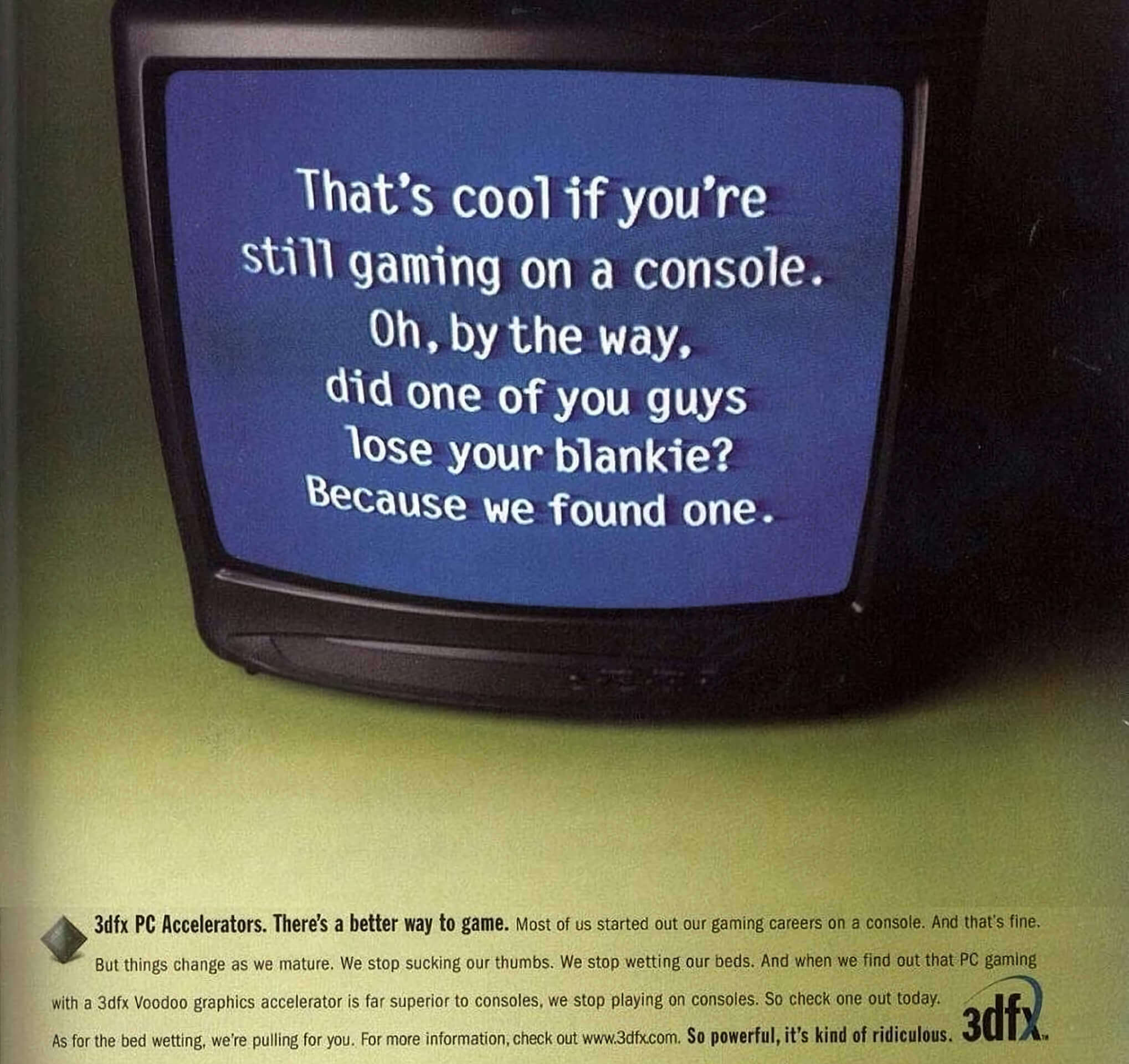

The showtime of 3Dfx's Voodoo3 serial arrived in 1999, backed by an extensive television receiver and print advertising campaign, a new logo – now with a small "d" – and vivid box art. The visitor's Voodoo3 and subsequent releases were not made available to hardware partners, finer turning third-party manufacturing partners into rivals that had no choice but to source chipsets from competitors such as Nvidia.

Diverse models featuring 3Dfx's Voodoo3 striking the market, catering to multiple price points. Nvidia returned fire that summer with the GeForce 256, which it billed as the world'southward start GPU (graphics processing unit).

The revolution that 3Dfx had ushered in three years earlier was now passing information technology past.

3Dfx's last hurrah came in the grade of the VSA-100 graphics processor that was to serve as the courage of the company'south next generation of cards. Only two, the Voodoo iv 4500 and Voodoo v 5500, would ever make information technology to marketplace.

But where 3dfx was once a catchword for raw performance, its strengths around this time laid in its full screen antialiasing prototype quality. The Voodoo five introduced T-buffer technology as an alternative to GeForce 256's T&L capabilities (transformation and lighting), past basically taking a few rendered frames and accumulation them into i epitome. This produced a slightly blurred motion picture that, when run in frame sequence, smoothed out the motion of the animation.

3Dfx's technology became the forerunner of many epitome quality enhancements seen today, like soft shadows and reflections, motion blur, likewise as depth of field blurring. That however was not enough to proceed them out of fiscal problem.

The Voodoo5 5000, which was to resemble the 5500 but with half the RAM, never launched. Neither did the Voodoo 5 6000, a hulking card packing four VSA-100 processors and 128MB of total memory. 3Dfx reportedly fabricated around 1,000 prototype cards for testing purposes, but again, none were ever sold to the public. Some of these fabulous pre-product cards did survive although very few working examples are known to exist today. They're considered among the holy grail of gaming hardware. If you lot can notice someone willing to office with theirs, be expected to pay several g dollars.

3Dfx pulled the trigger on a $186 one thousand thousand acquisition of graphics IP provider GigaPixel in March 2000 in an endeavor to help get products to marketplace faster just information technology proved to exist besides little, too late.

Shortly after the first Voodoo4 products hitting the marketplace later that year, 3Dfx'south creditors initiated bankruptcy proceedings. With few options, 3Dfx waved the white flag in Dec 2000 and sold most of its assets to Nvidia. Nearly 13 years later, 3Dfx's founders reunited for an oral history on the visitor hosted by the Computer History museum. It'due south an admittedly lengthy piece although if you've come this far, what's another ii and a one-half hours?

And if y'all're in the mood for a bit of retro gaming, y'all'll be happy to acquire that second-hand Voodoo-based video cards are readily bachelor through outlets like eBay. They're a fleck more expensive than you lot likely would have guessed (nostalgia will cost y'all), but they're upward for grabs if yous're in the market place.

On a personal note...

The December 1995 effect of GamePro mag featured a slice on DigiPen, a schoolhouse in Vancouver that teaches video game programming. News of this "Applied Computer Graphics" school couldn't have come at a improve time as my computer instructor had simply issued an assignment regarding our dream task and how information technology might chronicle to technology. I knew right then and there what I was destined to do.

I'd been into video games for every bit long as I tin can remember. For a cursory period in the mid-80s, my aunt owned and operated a video rental shop. It was the sort of shop yous'd observe in whatsoever modest town before Blockbuster monopolized the industry, with a respectable pick of movies and – most importantly for u.s. kids – Nintendo games. This just further solidified my interest in gaming.

I was fully enveloped by the late 90s, having laid claim to about every major panel on the market. Nary a week would go past that I didn't receive at least a few issues of the latest gaming mag in the postal service. Heck, I even circled release dates on my calendar and counted down the days until launch in earnest.

So in that location I was, an impressionable 13-year-erstwhile in computer class with his entire life already charted out. I'd finish class school, get accepted into DigiPen, graduate with some sort of degree and start living the dream of making video games.

In hindsight, that'due south probably how it would have played out had my other interest – the personal figurer – not intervened.

I got my offset computer in 1998 and it literally changed the entire trajectory of my life. I was still into gaming, mind yous, simply the focus immediately shifted from consoles to the PC and it didn't take long to realize that my AMD K6-2 CPU with 3DNow! instruction set needed some help in the graphics department.

Enter 3Dfx Interactive.

Source: https://www.techspot.com/article/2067-3dfx/

Posted by: villarrealcorne1967.blogspot.com

0 Response to "3Dfx Interactive: Gone But Not Forgotten"

Post a Comment